When any SIS student receives a PowerSchool notification of a poor summative grade, a typical response is to immediately criticize his or her teacher’s supposedly “unfair” grading system. Amid their groans, students often whine about the lack of a “curve” in their courses. However, if SIS implemented a bell-curve grading system, a 95 percent on an AP Biology test would likely become a 75 percent overnight.

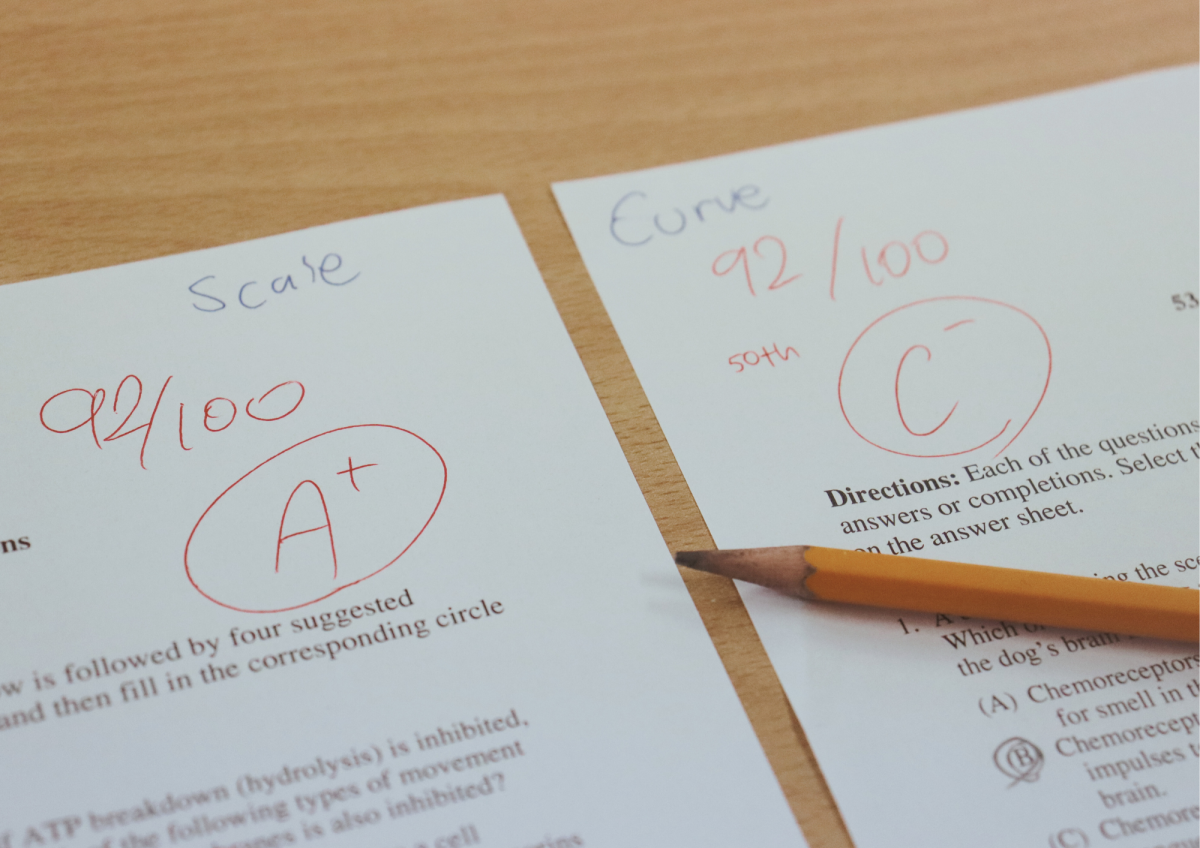

In reality, what most students want is a “scale” in their grades. A scaling grade system is very straightforward—the teacher assigns grades based on predetermined performance thresholds. For example, a teacher could create a scale for a relatively difficult summative assessment, establishing a direct conversion of a student’s raw score of 78 percent to their final grade of 92 percent.

“AP Biology has a scale because of the difficulty of the AP questions on the actual AP exam, and the expectation is not to get 100 percent on the AP exam,” Niko Lambert, AP Biology teacher who implements a scale, said. “I don’t want students to lose motivation right away from the beginning when they realize the difficulty level for AP Biology is much harder than ninth-grade biology. I think the scale is a way to encourage students to not give up even if they struggle on any particular exams.”

By contrast, curving is relative to the performance of everyone in the classroom. Even if a particular student receives an impressive score of 95 percent, if the majority in the class received higher scores, his or her score would “curve” onto the left side of the “bell-curve distribution.” Regardless of how objectively high the score is, curving the score could easily convert it to a 30 percent, relative to the performance of every student in the classroom. Likewise, a raw score of 70 percent could “curve” into a 98 percent if their performance exceeded that of most others.

“If you’re a teacher trying to see small differences between very skilled students, the bell curve is going to be a lot better, because one single point difference is going to make a massive curved score difference,” Donghyun Kim (12), five-year SIS student, said. “This is actually what the Korean education system does—relative grading. But, if I’m a student who wants to get good grades, I would much rather prefer a scaled score.”

In fact, the usage of the curve for assessing students in the Korean education system had fueled discontent in past years. Many criticized the system of alienating the majority of students into losers, with only a few emerging victorious from the harsh battlefield of academic competition. In 2021, the Ministry of Education announced a new system, the Gogyo Hakjumjae, that would implement a new grading rubric ranging from one to five, with rank one representing the top 10 percent of the class instead of the previous four percent, along with course selection options for students. Despite such attempts, the issues in the Korean education system continue to exist: Ham Young-ki of Educhang states that keeping the “pass/fail” system while implementing an unnecessary “comprehensive course selection” was a failure on the ministry’s part.

“SIS’s policy is that we don’t curve because an individual student’s grades should not be impacted by the performance of other students on the same assessment,” Chris DelVecchio, high school vice principal, said. “[Given] the diversity of destinations and what students here are preparing themselves to do next, there’s not really much of a logical benefit to having a ranking system… There’s not a limited number of academically capable people who can come out of school in any given year. Pretty much everybody that graduates from SIS has proven themselves to be academically capable for elite universities around the world.”