Science fiction is not what it used to be. Aficionados of the genre today have certainly heard this statement before: “Science fiction is less about humanity now than it was twenty years ago. It is more about the dry, inhuman technology and science.” While the statement has some truth to it, it doesn’t even come close to describing the true state of science fiction today.

I remember a genre that sought to encapsulate both the mortality of humanity and the limitlessness of imagination. I remember reading Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End and thinking to myself, “By God, this is powerful stuff.” Good works totally draw the reader into the world. Sure, the flashy tech and the fancy new gadgets always end up on the cover page, but the substance inside was a story about humans, written by humans, narrated by humans. If the author liked posing philosophical conundrums, like Isaac Asimov did, that story would have those very conundrums It was like the Sartre in space, Jane Austen at Jupiter, and Machiavelli on Mars. And it really made me something of a philosopher, physicist, and political scientist. A Nexialist, if you will.

Good science fiction took that stuff of the ether, vague philosophies and human stories, and added it to a touch of realism. It made you wonder about possibilities and dream. I was too young to have been there when it happened, but I know when Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” took to the screen, Joe Schmo would say to Jane Dough: “That’ll be us in ten years.” Maybe ten years was too optimistic of a prediction, but it was the sentiment that prevailed. Nobody was interested what kind of smart-watch would be around in 2010, but everybody was curious how Joe would raise his family on the Mars colony. It seems like we’ve taken a step back: there’s no colony, and Joe seems to cares more about his smart-watch than his family.

Taking all of this into account, you can imagine my surprise when legendary director Christopher Nolan of the “Inception” fame announced a milestone film project about the future of space. I won’t deny that I had high hopes for the film when I walked in the theater. Did I expect a masterpiece? Maybe, given Nolan’s reputation. Did I expect to find some bit of Frank Herbert or Ray Bradbury? Definitely. That was what all the hype was about after all, wasn’t it?

I was disappointed with “Interstellar.” Sure, it had that human element that everyone likes to talk about. But it didn’t really feel grounded in reality. Engineering majors left and right will constantly try to prove to me the realism in “Interstellar.” (Please stop trying to convince me that time dilution is real. I know it’s real.) I get that Nolan hired astronomers and physicists to put a black hole on screen. The talking robot marine is a great touch that’s reminiscent of SAL 9000 (HAL’s unfortunately less-known twin). But what “Interstellar” failed to do was to inspire something in me. It’s difficult to emotionally connect with Matthew McConaughey’s acid trip through time and space. Then the film just becomes more about the sci-fi jet and Tidal Wave Planet.

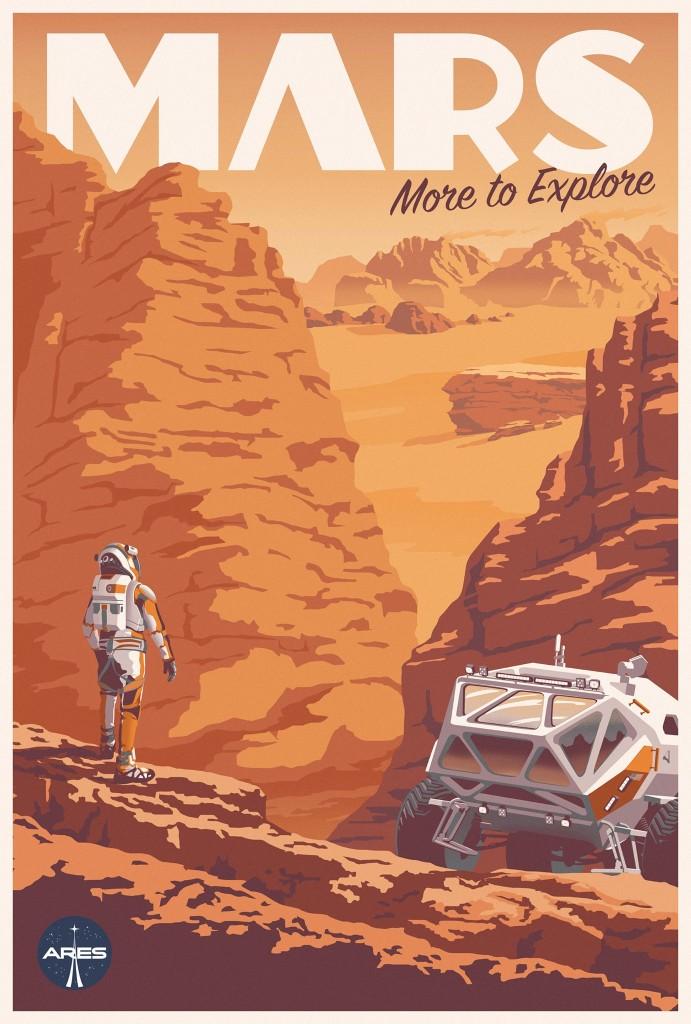

That’s why I think Ridley Scott’s most recent work, “The Martian,” is so magnificent. At its core, it’s a survival story of man versus nature—Robinson Crusoe set on Mars. It’s a story about camaraderie and determination, collaboration and innovation. The first thing “The Martian” did was revitalize Ridley Scott after a few recent setbacks like “Exodus: Gods and Kings” and “Prometheus.” The second thing it did was advertise engineering. There’s nothing like the full splendor of rocket launches and space missions being captured on camera to inspire the brilliant minds of tomorrow. No expense was spared—the cinematography and sound effects are chilling and majestic. I almost expected to see NASA credited as a producer when the credits rolled.

If you think you know the story because you saw the trailer, you’re in for a ride. If you think the scope of the film isn’t as grand as “Interstellar,” you’re mistaken: it’s one of the most gut-wrenching, visceral depictions of human resilience that I’ve ever seen on screen. Matt Damon seems to be very prone to being stranded on faraway planets these days in Hollywood, but his latest performance in “The Martian” was his best yet. If you think the film is formulaic, you’re right. It was adapted from a novel by Andy Weir, who wisely chose to use a formulaic survival story set in space. You don’t need to share the experience of being marooned to feel the connection. The formula works; it’s just human.

Finally, I can think of maybe one or two plot holes in the film. By plot hole, I don’t mean something that’s left unexplained. Yeah, you need radiation shielding to survive the long trip to Mars. Yeah, using human fecal waste to fertilize potatoes isn’t a thing yet. But they aren’t plot holes—they don’t take away from the film itself. Overall, the film is scientifically sound—it is grounded in reality. In fact, other than the high-tech touch-screen cockpits, “The Martian” is well within the realm of possibility that if only it wasn’t for Congress… but that’s another story. This film can be a journey into the near future for many people, just as it was a journey back to the Golden Age of science fiction for me.

“The Martian” was a blast from the past in terms of reminding me about good science fiction. It was also a look into the near future. As a victim of AP Physics, I felt that watching Matt Damon calculate orbital velocity was traumatic. So I mean it when I say that the film inspired me to think about the future of space exploration like no other film has, and I’m certain it will do the same for you.