By NICHOLAS KIM & JEREMIAH NAM

When walking through the streets of Apgujeong, visitors often note the proliferation of plastic surgery clinics and nightclubs that dot the landscape. Yet, hidden amidst this scenery, ubiquitous flyers are strewn across the pavement, underfoot. A casual observer might pass by without a second thought, but upon closer observation, their contents reveal the hidden, yet prolific world of college consulting in Korea.

These advertisements promise “profile shaping” and “extracurricular analysis,” along with various “additional services.” Below the promises are the success stories — students that the firm succeeded in sending to their dream schools. Conspicuously absent are students disappointed by a service that promised so much at so high a cost.

The annual college admissions process has become increasingly competitive as more people around the world apply to US colleges and universities. According to the Institute of International Education, nearly one million students were educated in US colleges and universities in 2015, up 10 percent from the previous year. To students who attend international schools like SIS, the process is an integral part of the high school experience––so much so that it often becomes the focal point of student life.

Despite this phenomenon, there is limited information on college consulting for those not directly involved in the system, and there are many questions left ambiguous and unanswered through the seemingly “hush-hush” grapevine of mutual friends. With a lack of credible information about the role of consultants, there is also a great deal of misunderstanding and stigma attached to the nature of the college consulting process in Korea. Hence, this investigative piece is dedicated to correcting misconceptions relating to services, pricing, and other factors involved in the college admission process, in an effort to shed light on a topic in which accurate information has not been clearly standardized.

Over the course of a month, Tiger Times researched this area through several means, approaching five consulting firms as prospective clients and conducting random surveys of students at SIS, as well as current university students, to provide insight into this often-unseen system. All sources and participants have been given pseudonyms to protect their identities; the consulting firms will be referred to as firm A, B, C, D, and E.

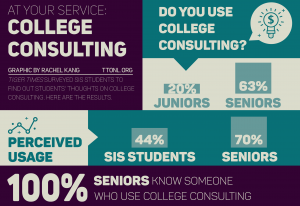

Survey results conducted throughout the SIS student population found that the frequency of students retaining these consulting services has a direct correlation with current grade-level. While less than 25 percent of the freshmen and sophomores interviewed say they use college consulting services, the number balloons to 70 percent for seniors. At the same time, when asked to guess the percentage of students using these services, estimates were on average 41 percent among non-seniors, and 63 percent among seniors.

Survey results have also revealed an incongruity in the qualitative perceptions that many students have of these firms. Some see outside consulting as an unnecessary or unfair service, a process that provides advantages to those willing to spend large sums of money. These skeptics see that firms are morphing the character of students into an ideal, vastly different from reality.

“I definitely felt a bit of shame in going through these services, and a lot of times I questioned if what I was doing was ethical,” said a Korea International School graduate. “The environment of is friendly and helpful, but underneath it all you cannot help but realize, especially after the entire experience and you get into the college, and you are around your peers who got into that college independently without these consulting firms, there is an underlying feeling of shame.”

Though some do doubt the ethics of the practice, the firms themselves proudly advertise their services. Most, if not all, tout the educational background of their employees, often claiming that graduates of top Ivy-league schools and prestigious and selective post-graduate programs work in their offices. However, these claims could not be verified, and questions remain whether they make a substantive difference to the level of consulting provided.

“Some consultants do have backgrounds in education, but others do not. Attending a university does not mean that you are qualified to advise students on admissions: the process is not osmosis. I have flown on an airplane and I cannot be a pilot; why would attending a specific university give you the qualifications for attending that school?” said Fredric Schneider, Dean of Students. “Universities look at you in the context of your school. If private consultants do not know you in the context of your school, how can they advise you on what to do?”

SIS currently provides services that are tailored to each individual and for the high school body. In particular, Mr. Schneider helps arrange and schedule visits from college representatives from different universities. Christopher Thomson and Barbara Conant, high school counselors, also talk to students in attempts to encourage attendance at these meetings. Yet not all of these services are properly utilized by upperclassmen who are preparing for the experience. In some instances, it seems that the firms have co-opted the college research process for students, providing a “personalized” list of recommended schools of which to apply.

“Many college representatives come to visit SIS, but unfortunately, students tend to only go to the universities that they have heard of before.” Mr. Schneider said. “A real consultant looks at your statistics and gives you a realistic assessment, instead of giving you a super competitive list nobody can guarantee. There is no such thing as a safety school.”

In addition to such concerns, a frequently recurring issue with these firms is the money they charge to students. Due to the volatility in pricing structures it was difficult to get a concrete value for the absolute price of all the services provided. Nevertheless, inquiries into the businesses revealed information on cost, and a pattern can be easily delineated. College consulting firms are businesses where preliminary prices for initial consulting agreements are set, on top of which additional fees are assessed according to the supplementary services each student requests. The more services a student requires, the higher the fee. For example, a look into consulting firm A found that price ranged considerably, with additional fees for each subsequent service that students request, including extra essay guidance and aid with extracurricular activities.

An expansive range of services are also evident in the firms, with many of them providing and assisting with essentials needed to apply to colleges. Extending past the five main aspects that selective colleges in the US assess (personal essays, SAT scores, high-school transcripts, teacher recommendations, and extracurricular activities), consulting firms also help create a profile that purports to find the student’s niche. Certain firms in particular go so far as to offer an extremely detailed look into the extracurricular aspect of a student’s application, such as internships, volunteer work, summer research programs, competitions, clubs, and personal projects like blogs or YouTube channels. One firm even contains a studio to accommodate the number of students interested in an Art major. Again, there is some variation in the types of services provided, but there is a clear effort evident in the nature of these firms to entice students with a diversity of majors and interests.

Consulting firms B and E claim to have an established limit for the number of students they advise from each school. In fact, firm E assured our reporter that they advise no more than two students from each school. The justification behind this system, as provided by the firm, is so that ideas and writing styles reflected in the application essays do not overlap from multiple students of the same school, which hints at the possibility of a third person intervening and assisting in the application process. This quota also reflects the competitive nature of college application and just how many students in international schools are currently involved in the process. In fact, this is further substantiated by surveys of a random sample of SIS students, with seniors reporting that 100% of them knew at least one person who pays for this service.

Others maintain that it is a benefit that overlooks some of the application processes, but in no way compromises its integrity. They see this specialized consulting as a means to maintain and advance in the frenzy of competition.

A SIS student, a senior, noted, “as far as I am aware, all they do is read over what you write or help you come up with possible essay topics so it gives you a third person perspective that is not your parents or your teacher. They don’t control every aspect of your life.”

Findings have generally supported the second perception, showcasing a business where overbearing control is not the norm and ultimately students have to do much of the driving themselves.

The truth is, despite consulting industry perceptions and myths, there lies a commonly agreed-upon characteristic of these firms: specifically, that their intervention in the application system raises questions as to its ethical practice. Even under systems where mentors simply look over the application process, many take issue with how these businesses give a monetized edge over students that do not have the resources to partake. The question is whether businesses have an ethical responsibility to withhold services which have been designed for students to construct themselves, and that question extends past the findings in this investigation and must be formed by the individual.

As a student body that will largely be heading overseas to attend university, the distance both physically and culturally in post-secondary education in the US is obvious. Students who receive college consulting services have overwhelmingly said that it provides a level of comfort that nothing else can. In this way, perhaps it is not so much the advice families pay for, rather than the peace of mind and comfort that comes with someone guiding them through the admissions process. Perhaps it is this service that truly creates a willingness to spend so much on admissions services. After all, what would be the cost of getting it “wrong?”